What are government bonds?

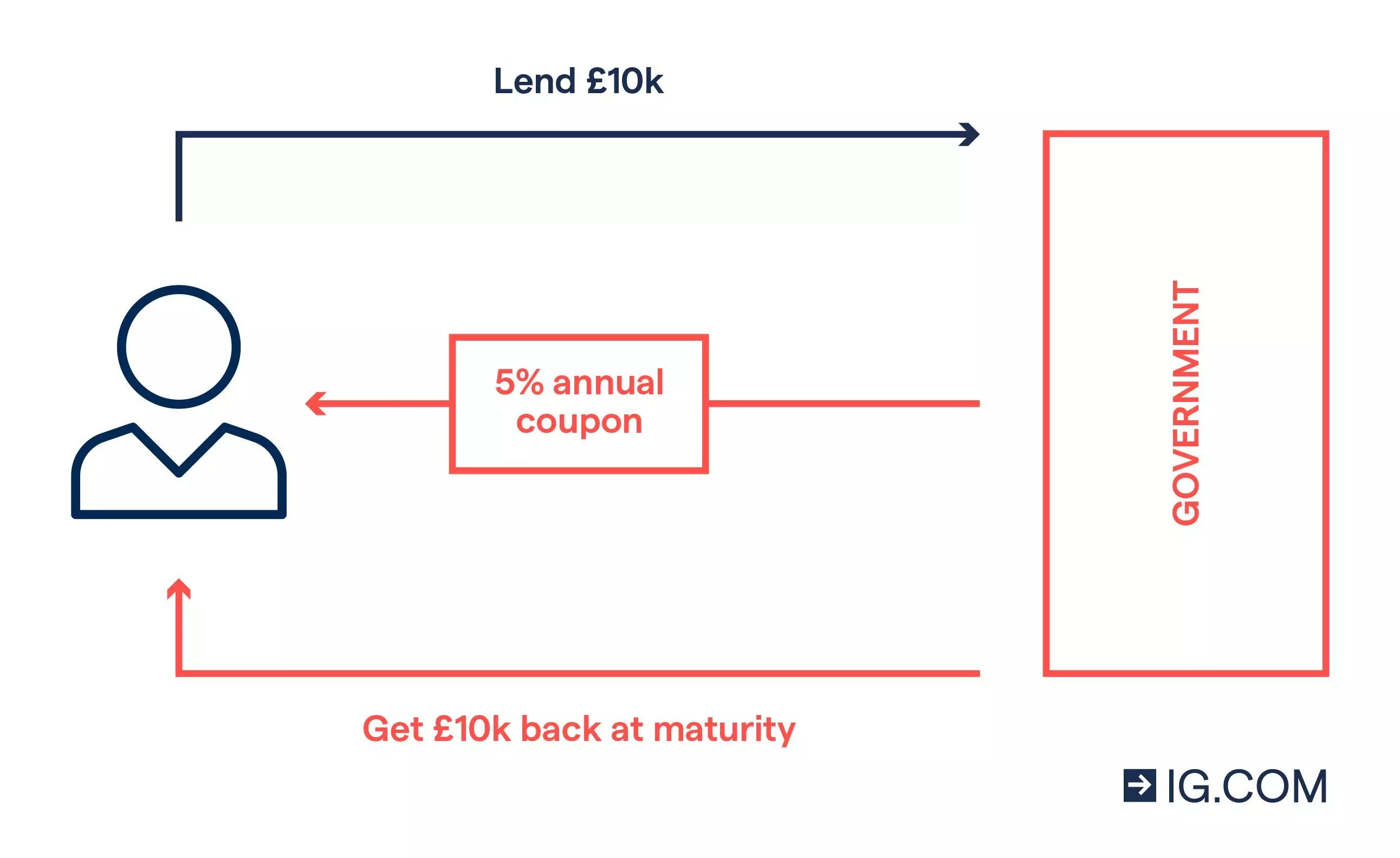

A government bond is a type of debt-based investment, where you loan money to a government in return for an agreed rate of interest. Governments use them to raise funds that can be spent on new projects or infrastructure, and investors can use them to get a set return paid at regular intervals.

In the US, government-issued bonds are known as Treasuries. In the UK, they’re called gilts. While all investment incurs risk, government bonds from established and stable economies are regarded as being comparatively low-risk investments.

How do government bonds work?

When you buy a government bond, you lend the government an agreed amount of money for an agreed period of time. In return, the government will pay you back a set level of interest at regular periods, known as the coupon. This makes bonds a fixed-income asset.

Once the bond expires, your original investment amount – called the principal – will be returned to you. The day on which you receive the principal is called the maturity date. Different bonds will come with different maturity dates – you could buy a bond that matures in less than a year, or one that matures in 30 years or more.

Key bond terms to remember

- Maturity: a bond’s time to maturity is the length of time until it expires and it makes its final payment – ie its active lifespan

- Principal: the principal amount – or ‘face value’ – of a bond is the amount it agrees to pay the bondholder, excluding coupons. In general, this is paid as a lump sum when the bond matures or expires

- Bond price: the issue price of a bond should, in theory, equal a bond’s face value as this is the full amount of the loan. But, the price of a bond on the secondary market – after it’s been issued – can fluctuate substantially depending on a variety of factors

- Coupon dates: coupon dates are the dates on which the bond issuer is required to pay the coupon. The bond will specify these, but as a matter of course, coupons are paid annually, semi-annually, quarterly or monthly

- Coupon rate: the coupon rate of a bond is the value of the bond’s coupon payments expressed as a percentage of the bond’s principal amount. For example, if the principal (or face value) of a bond is £1000, and it pays an annual coupon of £50, its coupon rate is 5% per annum. Coupon rates are generally annualised, so two payments of £25 will also return a 5% coupon rate

Government bond example

Say, for instance, that you invested £10,000 into a 10-year government bond with a 5% annual coupon. Each year, the government would pay you 5% of your £10,000 as interest (ie £500), and at the maturity date they would give you back your original £10,000.

Just like shares, government bonds can be held as an investment or sold on to other investors on the open market.

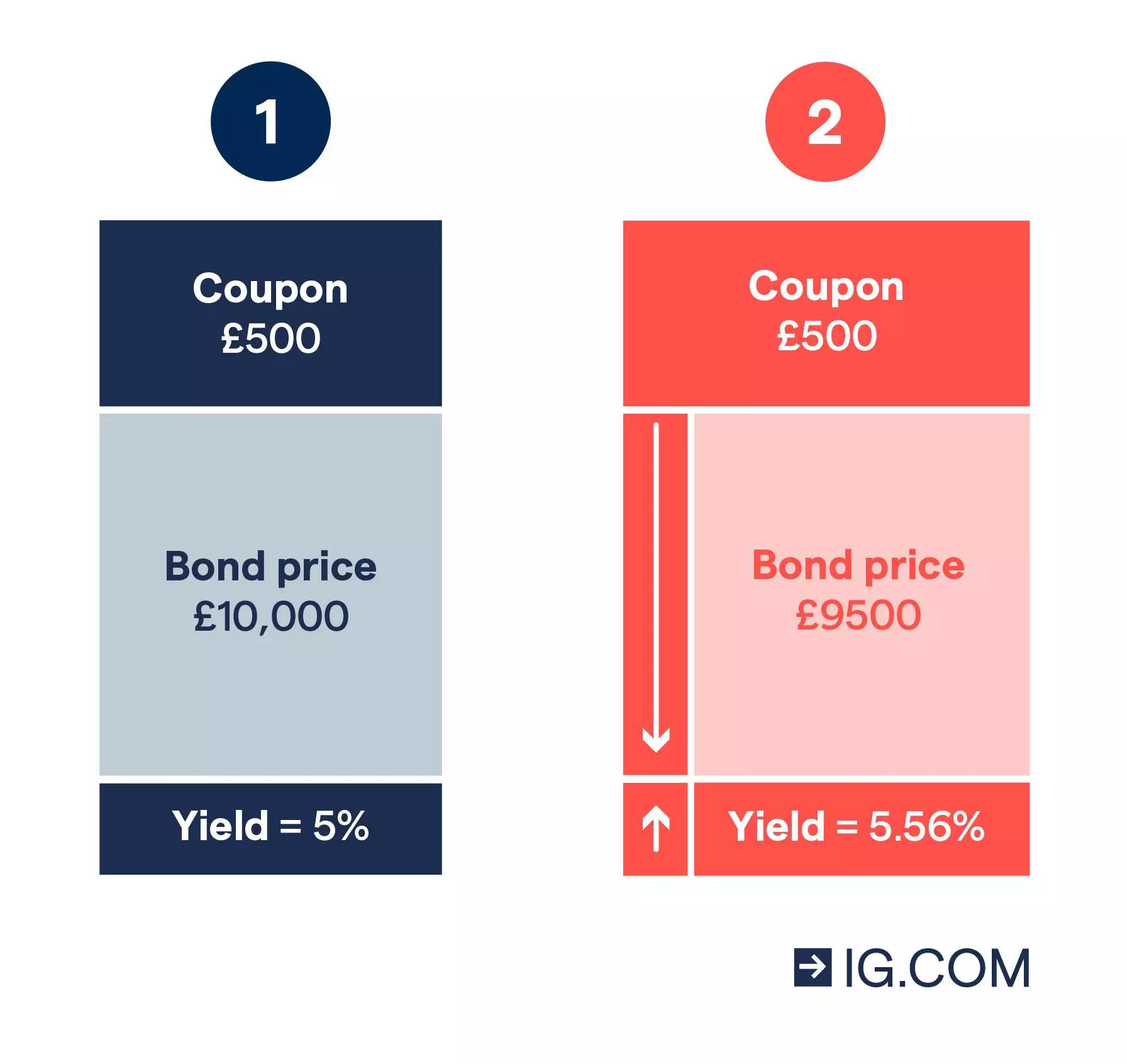

Using our above example, say that your 10-year bond is half way to maturity, and that you’ve spotted a better investment elsewhere. You want to sell your bond to another investor, but because better investment opportunities have arisen, your 5% coupon now looks a lot less attractive. To make up the shortfall, you might sell your bond for less than the £10,000 you originally invested – for example, £9500.

An investor buying the bond would still get the same coupon – £500. But their yield would be higher, because they paid less to get the same return. In this case, their current yield would be 5.56%.

A bond with a price that’s equal to its face value is said to be trading at par – if its price drops below par it’s said to be trading at a discount, and if its price rises above par it’s trading at a premium.

Bonds vs bond ETFs and funds

Bond ETFs and other bond investment funds use pooled funds to buy a selection of bonds - both government and corporate bonds. Shares in these funds then pay dividends from the coupons they receive. But, Bond ETFs and funds are complex investment vehicles because the bonds they hold may have different maturities, coupon rates and coupon dates.

Additionally, unlike bonds, bond ETF shares never mature or repay a principal amount on the value of your share purchase. Before you buy shares in a bond ETF, ensure that you understand what assets it holds and what the fund’s particular characteristics are.

With these important differences noted, bond ETFs offer certain benefits to shareholders:

- Regular income from dividends: bond ETFs pay dividends. This means that the coupons the fund receives from the bonds it holds are distributed to shareholders on a regular basis. These may not be a fixed amount, though, as coupons may differ in payment dates and values

- Low management fees: ETFs are often passively managed and have relatively low fees when compared to actively managed investment funds

- Wide exposure from a single position: bond ETFs frequently track a bond index (like the FTSE Actuaries UK Conventional Gilts All Stocks Index), giving you wide exposure to several bond variations from a single position

- Portfolio diversification: similar to holding bonds directly, bond ETFs bring asset class diversity to a stock portfolio, helping to mitigate some of the portfolio’s market risk

What are the types of government bond?

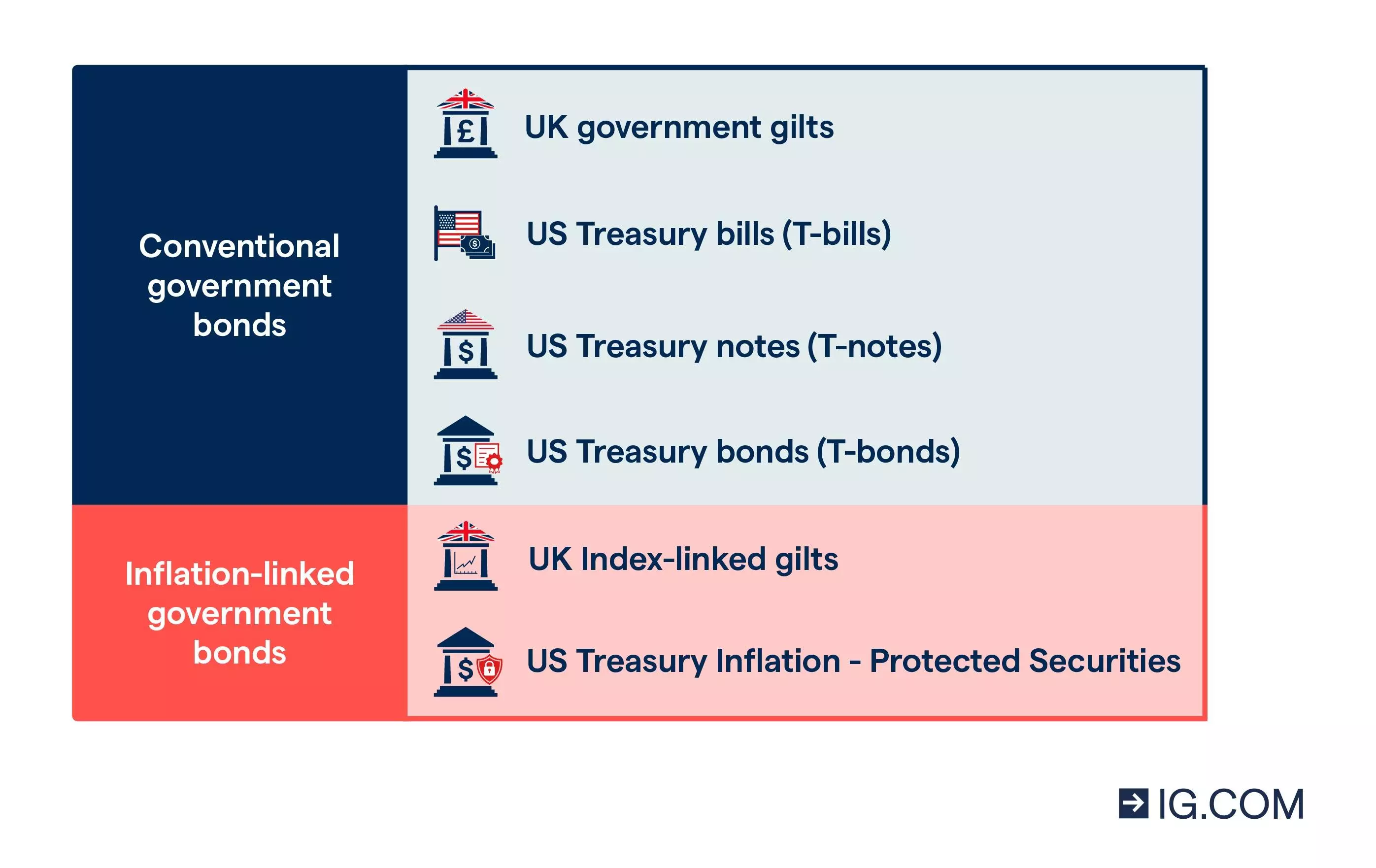

The terminology surrounding bonds can make things appear much more complicated than they actually are. That’s because each country that issues bonds uses different terms for them.

UK government bonds, for example, are referred to as gilts. The maturity of each gilt is listed in the name, so a UK government bond that matures in two years is called a two-year gilt.

In the US, meanwhile, bonds are referred to as Treasuries. They come in three broad categories, according to their maturity:

- Treasury bills (T-bills) expire in less than one year

- Treasury notes (T-notes) expire in one to ten years

- Treasury bonds (T-bonds) expire in more than ten years

Other countries will use different names for their bonds – so if you want to trade bonds from governments outside of the UK or US, it’s a good idea to research each market individually.

Index-linked bonds

You can also buy government bonds that don’t have fixed coupons – instead, the interest payments will move in line with inflation rates. In the UK, these are called index-linked gilts, and the coupon moves with the UK retail prices index (RPI). In the US, they are called Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS).

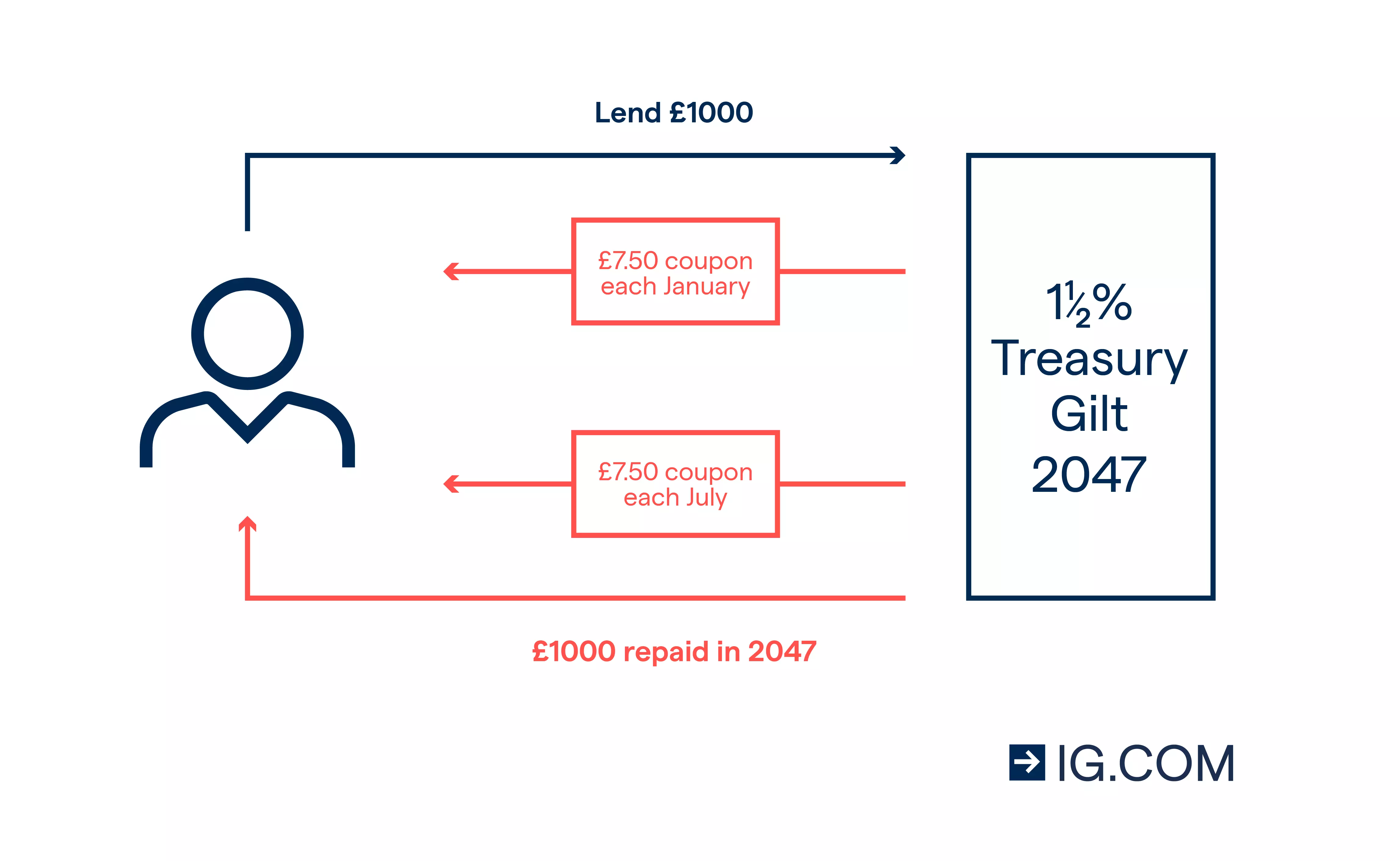

Example of a UK government gilt

An example of a conventional UK government gilt is the ‘1½% Treasury Gilt 2047’. The date of maturity on the bond is 2047, and the coupon rate is 1.5% per year. Here, you’d receive two equal coupon payments, six months apart. If you held £1000 nominal of 1½% Treasury Gilt 2047, you would receive two coupon payments of £7.50 each on 22 January and 22 July.

How to buy government bonds

How to invest in government bonds

When a government wants to issue bonds, it will usually do so via a bond auction, where the bond will be bought by large banks or financial institutions. Those institutions will then sell the bonds on, often to pension funds, other banks, and individual investors.

Although a wide range of bonds are listed on exchanges like the London Stock Exchange, they are primarily traded over-the-counter (OTC) through institutional broker-dealers.

To invest in the government bond market, you could either buy actual bonds or purchase shares in a bond ETF or fund. UK government gilts can be bought directly from HM Debt Management Office and from authorised agents.

How to invest in government bond ETFs and funds

To earn an income from dividends, or to diversify your portfolio, you could consider investing in bond ETFs. When investing in bond ETFs with us, you’ll buy shares through our share trading account.

Bond ETFs offer:

- Regular income from dividends

- Low management fees

- Wide exposure from a single position

- Portfolio diversification

With our share trading account, you can buy and sell bond ETFs from $0 commission per trade for domestic1 and international ETFs (0.7% FX fee applies to international trades).2

Our bond ETF offering includes:

How to trade government bond futures

To speculate on interest rates, or to hedge against interest rate risk and inflation, you could consider trading the government bond futures market. With us, you can do this by taking a position using CFDs.

With both, you would put down a small deposit (called margin) to open a larger position, but your profits and losses will be calculated on the position’s full size rather than your smaller margin amount.

It’s important to note that leveraged financial products are complex and carry inherent risk. While leverage enables you to gain more profit for less capital if you predict the market movement correctly, you can also lose far more if the market moves against you. So, unlike owning bonds outright, your loss isn’t limited to the bond’s underlying value.

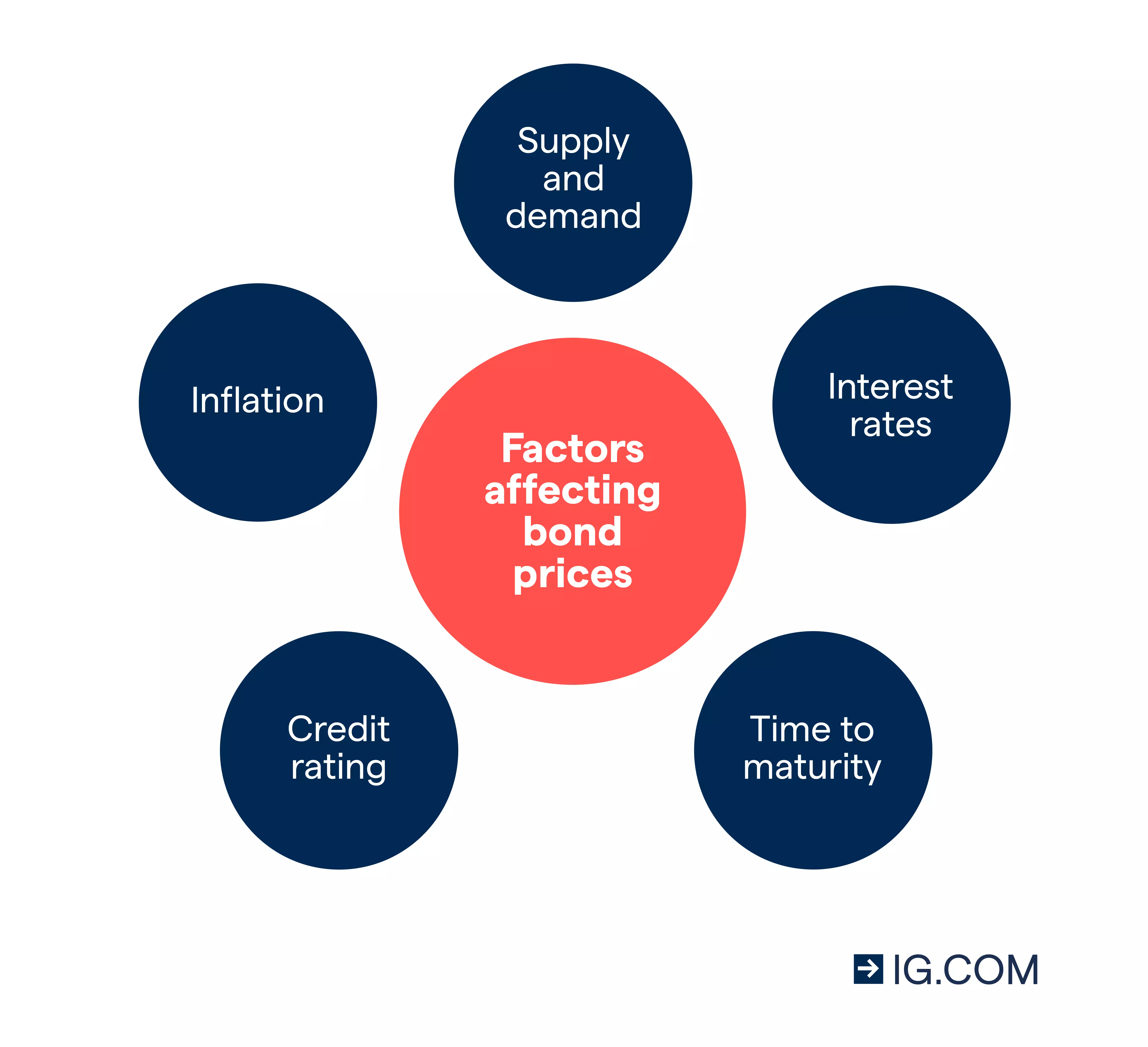

What affects the price of government bonds?

Supply and demand

As with all financial assets, government bond prices are dictated by supply and demand. The supply of government bonds is set by each government, who’ll issue new bonds as and when they’re needed.

Demand for bonds is dependent on whether the bond looks like an attractive investment.

Interest rates

Interest rates can have a major impact on the demand for bonds. If interest rates are lower than the coupon rate on a bond, demand for that bond will likely rise as it represents a better investment. But if interest rates rise above the coupon rate of the bond, demand will potentially drop.

How close the bond is to maturity

Newly issued government bonds will always be priced with current interest rates in mind. This means that they usually trade at or near their par value. By the time a bond has reached maturity, it’s just a pay out of the original loan – ie bonds move back towards their par values as they near this point.

The number of interest rate payments remaining before a bond matures will also have an impact on its price.

Credit ratings

Government bonds are usually viewed as low-risk investments, because the likelihood of a government defaulting on its loan payment tends to be low. But defaults can still happen, and a riskier bond will usually trade at a lower price than a bond with lower risk and a similar interest rate.

The main way of assessing the risk of a government defaulting is through its rating from the three main credit rating agencies – Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch Ratings.

Inflation

A high inflation rate is usually bad news for bondholders. There are two main reasons for this:

- The fixed coupon payment becomes less valuable to investors when the purchasing power of the coupon amount declines owing to inflation

- Interest rates are often increased by central monetary authorities like the Reserve Bank of Australia when high inflation sets in. Because interest rates and bond prices are inversely related, the higher interest rates result in a lower market price for the bond.

Why do people buy government bonds?

People invest in government bonds to:

- Diversify an existing stock portfolio

- Receive regular income from coupon payments or bond ETF dividends

People trade government bonds to:

- Speculate on interest rate movements

- Hedge against interest rate increases on existing bond investments

- Hedge against high inflation on existing fixed-income investments

Ready to trade or invest in government bonds? Discover our bond trading and investing platform.

Government bond risks

You might hear investors say that a government bond is a risk-free investment. Since a government can always print more money to meet its debts, the theory goes, you’ll always get your money back when the bond matures.

In reality, the picture is more complicated. Firstly, governments aren’t always able to produce more capital. And even when they can, it doesn’t prevent them from defaulting on loan payments. But aside from credit risk, there are a few other potential pitfalls to watch out for with government bonds: including risk from interest rates, inflation and currencies.

What is interest rate risk?

Interest rate risk is the potential that rising interest rates will cause the value of your bond to fall. This is because of the effect that high rates have on the opportunity cost of holding a bond when you could get a better return elsewhere.

What is inflation risk?

Inflation risk is the potential that rising inflation will cause the value of your bond to fall. If the rate of inflation rises above the coupon rate of your bond, then your investment will lose you money in real terms. Index-linked bonds are less exposed to inflation risk.

What is currency risk?

Currency risk only applies if you buy a government bond that pays out in a currency that is different to your reference currency. In this case, fluctuating exchange rates may cause the value of your investment to drop.

FAQs

How risky are government bonds?

Government bonds are guaranteed by the full faith and backing of their respective governments. It’s important to note, however, that even government bonds are subject to numerous risks, including credit risk.

What are the ways to trade government bonds?

- To trade government bond futures markets, open a CFD trading account

- To invest in bond ETFs yourself, open a share trading account

1 For all fees, please see our share trading cost and charges page.

2 $0 commission applies to clients who trade on the IG share trading account and opt for the default setting of ‘instant currency conversion’. Clients who choose to convert currencies manually will pay commission of 2 cents per share with a minimum charge of $10 on US stocks and, for European markets, we charge £10 / €10 per trade or 0.1%, whichever is higher. Other fees and charges may apply, please see our share trading cost and charges page.